This week, we read an article titled Linking Geology and Botany…a new approach, written by Jane L. Forsyth. This article studied the relationship between these two areas of study, and what we can do with that information moving forward.

- According to geology, Ohio can be divided into two sections. Although these sections aren’t perfect, they work well when assessing the relationship between geology and botany. The first of these sections is the western half of Ohio. This section is underlain with limestone. The other side is eastern Ohio, which is underlaid with sandstone, and shale to the west. Sandstone is a much more resistant rock and protects the more brittle shale underneath.

- Around 200 million years ago, there was an original sequence of sedimentary rock in Ohio. From bottom to top, it was layered as limestone, shale, and then sandstone. This created an arch with the crest being the oldest limestone layer, which extends north to south in western Ohio. The low-lying toe of the arch, composed of sandstone, is further east. An important river system that occupied the land was the Teays River, a preglacial river responsible for most of the erosion. This river was present for about 200 million years and continued to erode the last for most of that time. Teays was stopped, however, due to the advancement of the glaciers during the Ice Age.

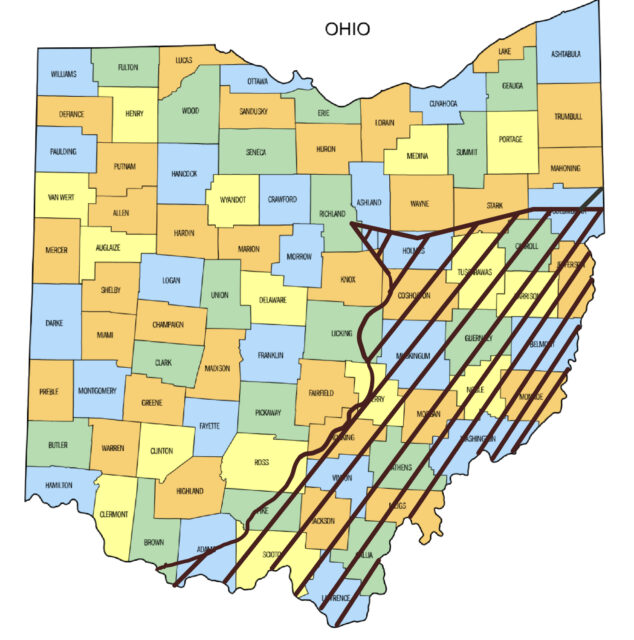

- Pleistocene glaciers enters Ohio a few hundred thousand years ago but were slowed down greatly by steep-sided sandhills, found in eastern Ohio. The Glaciers were not able to break the latitudinal boundary of what is now Canton, however, due to the limestone plains of western Ohio, the glaciers were able to extend to northern Kentucky.

Map of Ohio showcasing the glacial boundary. The hash marks represented the unglaciated region.

4. Glacial till is an unsorted mixture of silt, clay, sand, and boulders. All of this comes together through the melting of ice. This till occurs as a kind of blanket over the glaciated parts of Ohio. The composition is a reflection of the geologic materials that were picked up by the glaciers and deposited. This creates a difference in the materials of the glacial till of east and west Ohio. The till in Western Ohio is rich in lime and clay, which were in the limestone bedrock. The till in eastern Ohio contains little clay and lime, other than near the margins of siltstone hills.

5. The basic substrate for the plains of western Ohio is limey, clayey till. This allows for relatively impermeable soil, but is poorly drained and not well aerated. This means that although water does not soak into the soil very quickly, it remains there for a long time. The nutrient availability in this soil is abundant, however. In eastern Ohio, the sandstone bedrock produces a low-nutrient substrate, that is very acidic. There is also a supply of moisture, that is continuously available and cool, coming from springs. The shale underneath also has an acidic, low-nutrient substrate. This substrate, however, is impermeable, and rather than soaking in, water tends to run off, making it harder for the substrate to obtain moisture.

6. Plants have different substrate preferences and requirements. These tolerances vary greatly from plant to plant. Using this knowledge, we can predict what plants are going to be in a certain location. Some species of trees and shrubs are generally limited to limestone or limely substates. Some of these species include redbud (Cercis canadensis), snow trillium (Trillium nivale), hop hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana), nodding thistle (Caduus nutans), and blue ash(Fraxinus quadrangulata).

7. On the other hand, some plants prefer high-lime, clay-rich substrates. These can be developed in the glacial till of western Ohio. Some examples of plants that prefer this substrate are sugar maple (Acer saccharum), beech (Fagus grandifolia), swamp white oak(Quercus bicolor), white ash(Fraxinus americana), and shagbark hickory(Carya ovata).

8. Lastly, some plants are generally limited to and prefer the sandstone hills of eastern Ohio including mountain maple(Acer spicatum), trailing arbutus (Epigea repens), bellwort(Ulvularia perfoliata), hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), and scrub pine (Pinus virginiana).

9. The Major determinant of distribution is different for every plant. One example is sweet buckeye. This species of tree does not occur anywhere inside the glacial boundary. The reason for this is not known, but it is predicted to be due to problems with repopulation in the clayey, high-lime glacial tills. It is also possible that climate plays a role in why sweet buckeye is not found past the boundary. In comparison, Hemlock is also present in unglaciated eastern Ohio, however, unlike sweet buckeye, it extends to the north, past the glacial boundary. This could be because hemlock prefers cool, moist environments such as those found in valleys in the north. Another plant species found in the glacial boundary is the rhododendron. Rhododendrons are one of the several species that lived in the Appalachian highlands. From there, it migrated through the Teays River to southern Ohio. They still have distribution in this area.

After reading this article and understanding the new information that it gave us, we visited Battell Darby Metro Park. This site was perfect for limestone-loving plants, and we found several that thrive in those environments.

Common Name: American Hackberry

Scientific name: Celtis occidentalis

The American Hackberry is a broad-leaved tree with alternating simple leaves. It has long-pointed, coarse-toothed leaves, whose bases are mostly uneven.

Common name: Blue Ash

Scientific name: Celtis occidentalis

Blue Ash is a broad-leafed tree with opposite feather compound leaves. It has 7-11 leaflets, which are always toothed. The twigs are also square or four-lined.

Common name: Chinquapin Oak

Scientific name: Quercus muehlenbergii

Chinquapin oaks are broad-leafed trees with alternate simple leaves. Their leaves have 8-13 pairs of sharp teeth.

Common name: Fragrant Sumac

Scientific name: Rhus aromatica

Fragrant Sumac is a broad-leaved shrub with alternate compound leaves. It has 3-parted large toothed leaves, that when crushed, have an unpleasant odor. The fruits are beanlike, and the buds are visible and hairless.

There were also several invasive species that we found along the way during our trip.

Common name: Amur Honeysuckle

Scientific name: Lonicera maackii

Honeysuckle is a broad-leaved plant with opposite simple leaves. It has white flowers, that fade to yellow, and five petals, four of which are fused.

Common name: Garlic Mustard

Scientific name: Alliaria petilolata

Garlic Mustard is a wildflower with alternative leaves. It has leaves that are coarsely toothed and long-stalked. It also has white flowers, that measure ¼-⅓ inch wide.

I was tasked with finding two Apiaceae at Battelle Darby as well. Although there was a lot to choose from, these are the ones that caught my eye.

Common name: Aniseroot

Scientific name: Osmorhiza longistylis

Aniseroot is a wildflower with alternate leaves. It has styles that are longer than the petals and tiny white flowers in umbels.

Common name: Black snakeroot

Scientific name: Sanicula marilandica

Black Snakeroot is a wildflower with alternate leaves. It has 5 leaflets that appear to be seven due to them being deeply cleft. It also has small, greenish flowers.